For a while now, I have been wanting to write about a patch of rocky terrain that exerts a powerful hold on the imagination — my own and that of many others before me. Over time, the harsh weather conditions in a tiny corner of northeastern Spain have created a geological dreamscape with extraordinary, weathered rock formations that have an almost hallucinatory ability to shape-shift, depending on weather conditions, the position of the sun and, I would be tempted to add, the mental state of the observer.

Here is much to see here that resembles the contents of a dream, or an hallucination. I will expand on this below. Meanwhile, the Wikipedia entry puts it, more prosaically, as follows:

The Cap de Creus (Cabo de Creus in Spanish) is a peninsula and a headland located at the far northeast of Catalonia, some 25 kilometres (16 mi) south from the French border. The cape lies in the municipal area of Cadaqués, and the nearest large town is Figueres, the capital of the Alt Empordà and the birthplace of Salvador Dalí. Cap de Creus is the easternmost point of Catalonia and therefore of mainland Spain and the Iberian Peninsula.

Strange, is it not, that in an otherwise geographical description the name of Salvador Dalí crops up, as it does with insistent frequency for any visitor to the area?Continuing the programme of self-promotion initiated with considerable success by Dalí himself, it is now impossible to visit the Empordà without being reminded almost constantly that you are, in fact, entering Dalíland.

Dalíland

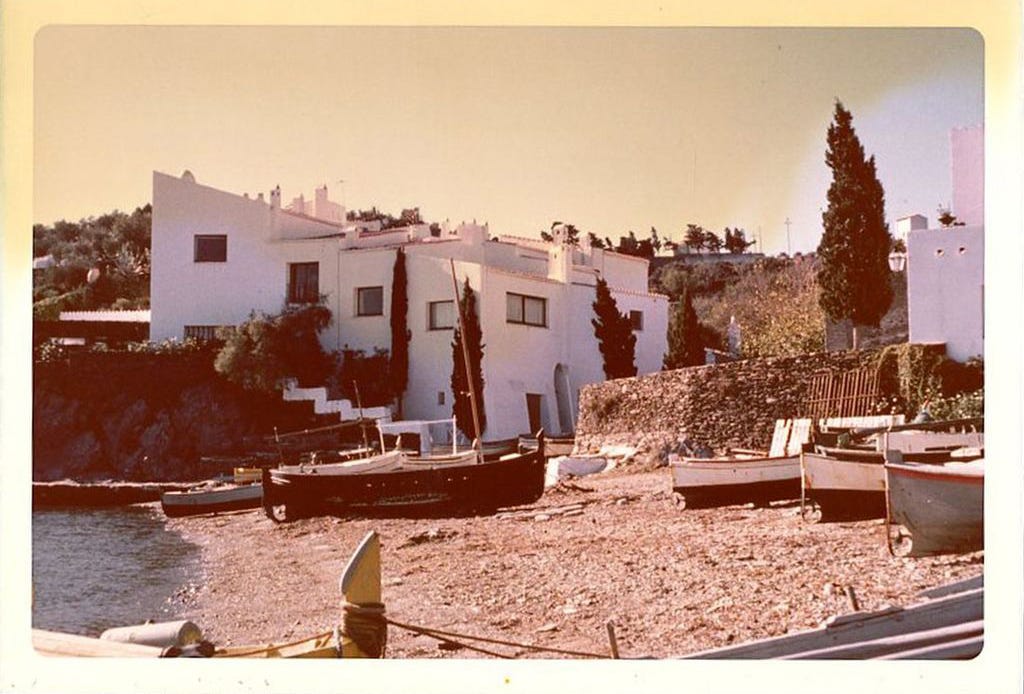

This is not such a problem, if you accept the fact that Dalí’s relentless egotism and shameless self-promotion not only served the artist well, but has also proved to be a major draw for the region, notably for the towns most associated with him — Figueres, the city of his birth, and Cadaquès, or more specifically Port Lligat, where he eventually made his home with his wife Gala, a woman as relentless in the pursuit of financial gain as Dalí himself, and with a sexual appetite to boot (though not with regard to her husband, who would watch Gala’s prolific copulations from a secret hiding place).

Quite apart from these domestic details, the lives of Dalí and his beloved, tyrannical Gala, have been set out for all to relish in the 2022 movie Dalíland, which, despite some unflattering reviews, I thought was rather good.

A confession: when I was about thirteen I had a poster of The Metamorphosis of Narcissus on my bedroom wall. That, of course, was long before I came upon George Orwell’s acid dismissal of the artist:

What Dali has done and what he has imagined is debatable, but in his outlook, his character, the bedrock decency of a human being does not exist. He is as anti-social as a flea. Clearly, such people are undesirable, and a society in which they can flourish has something wrong with it.

However, character aside — and given the revelations in Anna Funder’s Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, I rather doubt Orwell was in any position to take the moral high ground — it is interesting to learn how Dalí made use of the landscape to furnish his work.

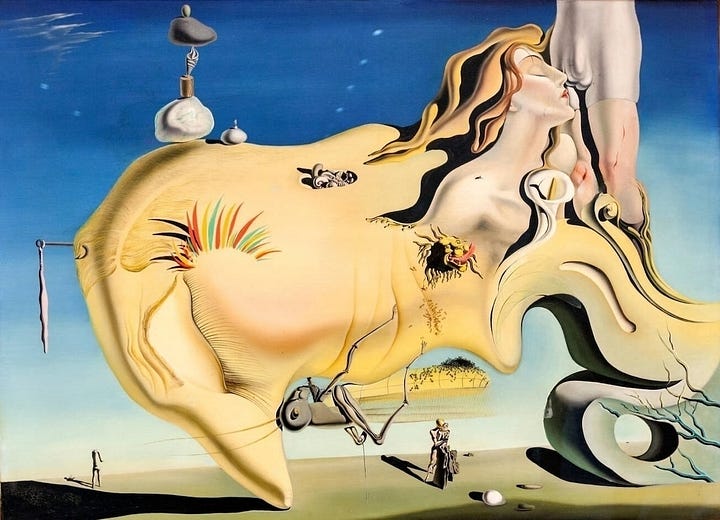

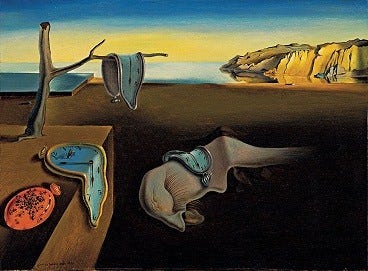

Two of his best-known paintings can be geo-located to parts of Tudela: The Great Masturbator (above) is based on the shape of a rock known as the Cavaliera or Cavaller (knight) while the famous melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory (below) are set against the outline of the coast at the Cap de Creus itself.

With regard to this second painting, the art historian Dawn Adès has written:

The soft watches are an unconscious symbol of the relativity of space and time, a Surrealist meditation on the collapse of our notions of a fixed cosmic order.

Such an interpretation might suggests that Dalí was incorporating an understanding of the world as suggested by Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. When questioned by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Ilya Prigogine whether this was the case, Dalí replied that the soft watches were not inspired by the theory of relativity, but by a surrealist perception of a Camembert melting in the sun. Touché!

However, believe it or not, this is not a post about Dali so much as the landscape that helped make him the painter that he was. It is the Cap de Creus that concerns me, or most specifically Tudela, which is the name given to the area adjoining the cape.

Tudela natural park

Tudela is now part of a natural park protected by the state. But it was not always thus. Back in the day it was the site of as legendary Club Med — one of the first all-inclusive holiday resorts in Europe. The Club Med at Tudela was set up in 1962 and aimed at mostly French tourists to provide a relaxing, active, and convivial holiday experience, imitating, after a fashion, the design and layout of a local fishing village.

Or, as the website of the Tudela-Culip (Club Med) restoration project rather caustically summarises:

Club Med was constructed on the easternmost tip of the Iberian Peninsula in one of the windiest and most northern exposed corners of the nation. Club Med was constructed as a private holiday village with 400 rooms that accommodated around 900 visitors in summertime. Life at Club Med was primitive, and meant to foster a relationship with nature.

During the summer of 2003, Club Med was shut down permanently. In 2005, the Spanish Ministry of Environment acquired the 200-hectare site and initiated a restoration program that took place over the following three years.

By 2010, the former Club Med complex had undergone a process of total dismantling, its ecological status was brought to the fore, and an ambitious public landscape project was launched to reimagine and reconnect people with the area. The initiative became the largest coastal deconstruction and environmental restoration undertaking in the Mediterranean to date.

I must say, this has been achieved with remarkable success. While very little remains to remind us that this was once a holiday village, I did pick up a powerful sense of entering a ghost town, and the striking rock formations only added to that strangeness, as though entering an alien landscape that had only recently been abandoned by its mysterious inhabitants.

Walking in Tudela

On April 4 this year, my wife’s birthday, we walked through Tudela, before going to eat at the Cap de Creus Restaurant, on the peninsula’s far edge. The walk, on a crystalline spring day, was exceptional in that it induced in both of us a sense of strange detachment from reality. The landscape assisted in this, obviously, but the notion of walking through a ghost-place, which had once been the site of a busy, sprawling holiday resort — of which barely a trace remained — only added to the pervasive sense of weirdness.

We make our way along a pathway that descends to the shore, marked at various stages along the route by rock shapes that demand our attention, such is their weathered strangeness. We invent names for the different figures: the lioness, the rhino, the camel’s head and the startled iguana. (I later learn that the shapes have other names and that my startled iguana is known as the Tudela Eagle). Along the way samphire, juniper, rosemary, and a whole host of cacti sprout from the volcanic rock.

According to David Bramwell, writing in The Guardian about this area:

The weirdness of this landscape is a result of northerly metamorphic and granite rocks — shale and pegmatite — mashed up when the Pyrenees were formed and then exposed to seawater and the corrosive effects of the northerly tramontana winds. Cream and golden boulders, looking like folded dough, sit among dark jagged slate with honeycomb weathering. Small multitudinous crevices look like hooded eye sockets of myriad skulls, all watching me. The hills do appear to have eyes.

The tramuntana wind, I might add, does more than corrode the landscape; it affects people’s minds. The wind has secured a place in local folklore and it is said that spending too long alone when the tramuntana blows can drive a person mad.

And yes, those crevices in the rock that resemble vacant eye-sockets: it feels as though we are being watched, but by whom, or what?

Walking through this phantasmagorical landscape induces an elevated sense of awareness, perhaps veering on the paranoid — but running in parallel to a deep sense of connection to the place’s history, its years as a holiday resort, and far, far beyond, to the Cretaceous era, when dinosaurs roamed these shores.

The restaurant at the end of the world

At the very end of the peninsula sits a lighthouse that dates from the year 1853 and adjacent to it, in the old administrative building is the Cap de Creus restaurant (owned by a British man, Chris Little). We had been meaning to go to this place — which came highly recommended by friends — for some time, but in the way of such things, had never got round to it.

It could not have been better: the service was friendly, and the food — we chose an Arròs a la cassola de marisc (a seafood paella) — was excellent. We ate our lunch a little late, even by Spanish standards, at 5 pm, but this was no problem, and the place was practically empty. We sat inside, with a view over the terrace, and the peninsula’s edge.

The message running though my mind on repeat while driving home afterwards was that virtually nothing here was quite what it seemed and that whatever you do see might well be something else. As Ian Gibson puts it in his excellent book The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí:

the landscape of the Upper Empordà that Dalí always admired fanatically from childhood and with which he will always be associated: Cadaqués, Port Lligat and the mineral wilderness of Cape Creus, that weird theatre of optical illusions which taught him that something can be something else . . .

Richard Gwyn is a writer and translator from Wales. His books include The Color of a Dog Running Away, The Vagabond’s Breakfast, The Blue Tent and Ambassador of Nowhere. For many years he led the graduate programmes in Creative & Critical Writing at Cardiff University, Wales. Information about his books, as well as articles, interviews etc can be found at https://richardgwyn.com or by clicking here.

Thank you Richard, I love your vivid writing and the journey I go on as I read.