Borges, Recursion and the Multiverse: Some Reflections (Part One)

Back in April, over a couple of entries, I wrote about recursion, spirals, fractals and related topics. My intention was to provide some context for a longer piece, that was originally written in Spanish and delivered at the 2023 Festival Borges, held in Buenos Aires under the title, Reflexiones sobre Borges, la recursividad y la hipótesis de los mundos paralelos. If you wish to hear a recording of that talk, it is available at the Festival Borges Youtube page here.

An English version appeared in PN Review in January this year, and I am now making it available for Raids on the Underworld. The first part follows below, and the article will conclude with the next post.

Borges, Recursion and the Multiverse: Some Reflections

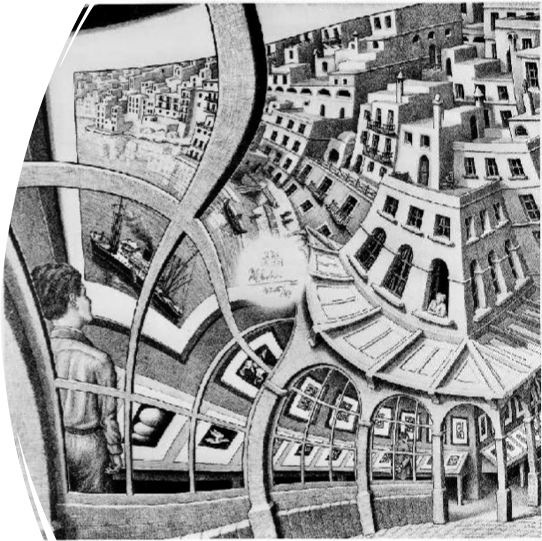

In his essay ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ (1939), Borges states that he can trace his first notion of the problem of infinity to a large biscuit tin that lent ‘mystery and vertigo’ to his childhood. ‘On the side of this unusual object,’ he writes, ‘there was a Japanese scene; I cannot remember the children or warriors depicted there, but I do remember that in a corner of that image the same biscuit tin reappeared with the same picture, and within it the same picture again, and so on (at least, potentially) into infinity . . .’[1]

This childhood experience of Borges’, in turn, evokes the vertigo the reader might feel before the various mysteries and labyrinths, the doublings and redoublings, and the recursive modes of narration that populate so many of the author’s stories. And it is this notion of recursion (or recurrent self-referentiality) that I wish to address and explore today.

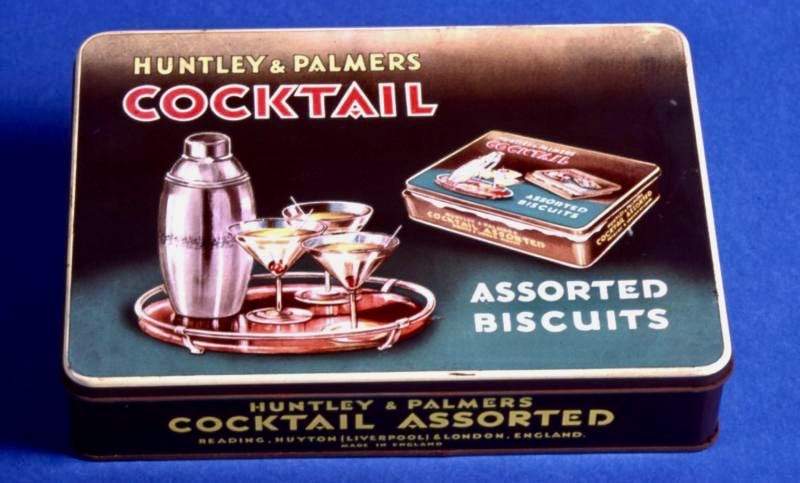

Of course, I don’t know what biscuit tin Borges had in mind, but I definitely remember this one, from my own childhood, which, like his, contains on the lid an image of itself, and within that image another, and so on ad infinitum. Like the young Borges, I remember being enthralled by the image.

A dozen or so years ago I was invited by the Argentine newspaper Clarín to write a piece commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Borges’ death. At around the same time, as chance would have it, I wrote a piece for the British newspaper The Independent for their series ‘Book of a Lifetime’, in which writers were invited to contribute short summaries of a favourite book. I chose Borges’ Fictions, and claimed that ‘other books have had a powerful impact on me, but none marked a turning-point in my understanding of the world and the written word in quite the same way.’ In both articles I began by describing the circumstances in which I was living when I first came across the work of the Argentine author, more or less as I record them here.

I discovered Borges’s short stories at the age of eighteen, when I was living in an abandoned shepherd’s hut at the foot of a mountain named Keratókambos, on the island of Crete. I found the place while exploring a deserted stretch of the south coast of the island, and moved in for the summer. I had a few books with me; I had just devoured The Brothers Karamazov and The Magic Mountain in rapid succession, and the brevity and intensity of Borges’s writing came as a revelation. Borges himself had something to say about big novels, as he articulated in the Prologue to Ficciones (1944):

The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoversishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books exist and then to offer a résumé, a commentary. [2]

The idea that instead of writing voluminous books we can simply pretend that they exist had a profound appeal to the budding writer in me, horrified at the interminable exposition of those mighty tomes by Dostoyevsky and Mann. Borges’s ludic style and brevity were much more attractive, and there was something enormously liberating, a kind of weightlessness, to the idea that by minimising the word count we might invoke extraordinary worlds without having to set them down with wearisome description, endless exposition and fatuous dialogue.

If only things were so simple. The brevity of a literary work does not diminish its complexity, and the worlds one encounters in Borges’s compact stories contain multitudes.

Fiction within Fiction

But more than anything else, all those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes — a recurring motif in Borges’s work — or that our universe is only one in a multiplicity of possible universes; or, less appealingly, that rather than being the proprietors of our own consciousness, we are being dreamed by some other entity. These are not comfortable ideas to live with, pushing, as they do, at the edges of comprehension. Always dissatisfied with received wisdoms, these ideas took a hold on me early in life, and I have never abandoned them, nor felt inclined to do so.

Borges concludes his essay on ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ with a summary of Flann O’Brien’s novel, At Swim-Two-Birds (which, it might be noted, he reviewed in the magazine El Hogar only six months after it first appeared in English), in which a young student from Dublin writes a novel about a publican from that city, who in turn writes a novel about his customers, one of whom is the student author; and he quotes Schopenhauer’s comment, ‘that dreaming and wakefulness are the pages of a single book, and that to read them in order is to live, and to leaf through them at random, to dream. Paintings within paintings and books that branch off into other books help us sense this oneness.’ In other words, the perspective that one story was a vehicle for other stories, and that the process could become one of unlimited recursion, was established quite early in the writer’s career, and over time it became a hallmark of his literary oeuvre.

A fundamental principle within the study of linguistics is that, in spoken language, an idea can be contained within an idea, a phrase within a phrase. This forms the basis of recursion in grammar. Noam Chomsky has claimed that it is the essential tool that underlies all of the creativity of human language. In theory, according to Chomsky, an infinitely long, recursive sentence is possible, since there is no limit to the mind’s capacity to embed one thought within another. Our language is recursive because our minds are recursive.

A parody of the opening sentence of a now-forgotten novel, Paul Clifford, by the 19th-century English novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, might serve as an initial illustration of recursion — ‘It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain: “Tell us a story!” And this is the story the captain told: “It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain, “Tell us a story!” And this is the story the captain told: “It was a dark and stormy night . . .”’

Another exercise in recursion would be the English nursery rhyme about an old lady who swallows a fly, which, as the song’s chorus repeats ‘wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her’. The unfortunate woman decides to swallow a spider in order to catch the fly, and then successively, a bird to catch the spider, a cat to catch the bird, a dog to catch the cat, and so on in a theoretically infinite number of permutations.

This gruesome little song neatly exemplifies the nature of recursion and, as I discovered, is even used an an illustration in a computer science programming manual on that topic.

An article on recursive thinking in American Scientist points out that the realisation that one has thoughts about one’s own thoughts itself constitutes a theory of mind. [3] René Descartes is renowned for the phrase cogito, ergo sum (although he actually wrote ‘je pense, donc je suis’: I think, therefore I am). Descartes presented this utterance as proof of his own existence, and although he sometimes doubted it, the doubt was itself a mode of thinking, so his real existence was not in doubt. The phrase is fundamentally recursive, since it involves not only thinking, but thinking about thinking.

Remembering a particular episode from one’s own life suggests a recursive projection of oneself out of the present moment. In the novel A la recherché du temps perdu, Marcel Proust returns to various projections of episodic memory, including the famous moment when the taste of a petite madeleine evokes the memory of a past event in the narrator’s mind.

In terms of the present text, we might consider as recursive the references I made a few moments ago, when I said that I started an article in Clarín twelve years ago with (almost) the same words that I used today, or when I recited the words: ‘All those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes.’

The notion of recursion is also the driving force behind fractals, complex patterns that are self-replicating across different scales. Fractals are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop. It has been claimed that the coast of Brittany has the characteristics of a fractal, for example, and we are all familiar with those windmilling patterns used to illustrate fractals, with images reminiscent of the hippy era and psychedelic drugs.

Once I begin to seek out instances of recursion in the works of Borges, Google leads me down a rabbit hole of articles on Borges and the infinite, Borges and Buddhism, Borges and quantum mechanics, Borges and the multiverse, as well, of course, as better known works on the writer, such as Guillermo Martínez’s study, Borges and Mathematics. It is as if, for my sins, I have stepped inside the Library of Babel, given that the internet is the ultimate manifestation of that accursed and infinite library, and itself an unparalleled example of recursion. The Library of Babel has also been represented as a fractal, or a series of fractals, in the work of various artists, and the creators of one website — the babel image archives — uses images instead of letters of the alphabet to reproduce, as its creators claim, every image that ever has been or could be created within its chosen colour palette.

Recursive Objects

In Martínez’s book there is much to give us pause for thought. Of particular note, in the first of his essays, is a reference to what he calls recursive objects:

It is possible to isolate this curious property of infinity and apply it to other objects or other situations in which a part of the object contains key information to the whole. We’ll call them recursive objects.

For example, he reminds us that ‘from a biological point of view, a human being is a recursive object. A single human cell is enough to generate a clone . . . Certain mosaics are clearly recursive objects: in particular, those in which the design inherent in the first few tiles is repeated throughout.’ Martínez is a mathematician, as well as a novelist, and there is, among his various explanations — which we do not have time to go into now — an account of mathematical infinity in which it is shown that the whole is not necessarily greater than each of the parts: ‘There are certain parts that are as great as the whole. There are parts that are equivalent to the whole.’[4]

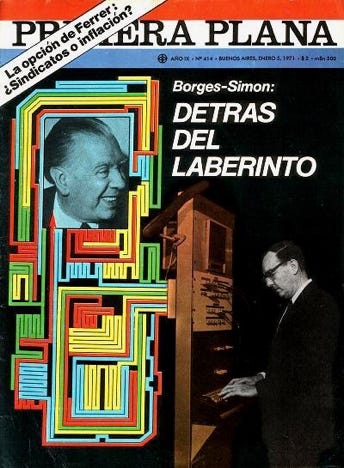

In the works of Borges, the supreme recursive objects are libraries and labyrinths. I have made reference to ‘The Library of Babel’ – itself a labyrinth – and we know from various sources that the labyrinth was a foundational myth for young Georgie, as he was known by his family. In 1971 Borges was interviewed by the Economics Nobel laureate and renowned computer scientist Herbert Simon, one of the founding investigators of Artificial Intelligence, who was visiting Buenos Aires. This improbable meeting of minds was set up at Simon’s request. The conversation took place in English. In attendance, but not participating, was the writer Gabriel Zadunaisky, who recorded and translated the interview for the weekly journal Primera Plana.[5]

At the start of the interview, Simon asks Borges about the origins of his fascination with labyrinths, to which Borges replies that he could remember having seen an engraving of a labyrinth ‘in a French book’. Borges tells Simon that he used to gaze at this engraving of the labyrinth, and adds, a little ironically, that if he had had a magnifying glass, he might have been able to make out the shape of the Minotaur, within its corridors. Simon, playing along, asks him if he ever found it, to which Borges replies, ‘As a matter of fact my eyesight was never very good.’ And then, a little incongruously: ‘Later I discovered a little about life’s complexity, as if it were a game. I’m not talking about chess now’. At least, this appears to be what he says. In the text published by Primera Plana, the words are ‘No me refiero al ajedrez en este caso’ (I’m not referring to chess here) but, bizarrely, in the Rodríguez Monegal biography (written in English) they become the exact opposite: ‘I’m talking about chess now.’ There follows a passage in the interview in which Borges remarks on the play of words (in English) by which ‘maze’ is included within the word ‘amazement’, and he comments to Simon: ‘That’s the way that I regard life. A continuous amazement. A continuous bifurcation of the labyrinth.’[6] I would ask you to hang onto this remark. We will return to it shortly.

Guillermo Martínez also reminds us that in Borges’s short parable, ‘On Exactitude in Science’, there is another example of recursion, when the map of a single province occupies the space it was originally designed to represent, and with the years it falls apart, until its tattered ruins ‘are inhabited by animals and beggars.’[7] Furthermore, Borges refers several times in his works to the map of Josiah Royce, perfectly traced on a small tract of English soil, and which is so precise that it contains within it a map of itself, which in turn contains a map of the map, and so on.

We might add to these examples the recursivity of A Thousand and One Nights that Borges references in both ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ as well as in ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction.’ In this second text, as Borges reminds us, the murderous king appears to himself in one of the stories he is being told. To quote from the essay:

None of them is as disturbing as that of night 602, a piece of magic among the nights. On that strange night, the king hears his own story from the queen’s lips. He hears the beginning of the story, which includes all the others, and also – monstrously – itself. Does the reader have a clear sense of the vast possibility held out by this interpolation, its peculiar danger? Were the queen to persist, the immobile king would forever listen to the truncated story of the thousand and one nights, now infinite and circular . . . In The Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade tells many stories; one of them is, almost, the story of The Thousand and One Nights. [8]

Incidentally, Julio Cortázar’s short story ‘The Continuity of Parks’ addresses the same notion, which is certainly no coincidence.